What are the differences between ABAC vs RBAC?

Implementing ABAC with Oso Cloud

ABAC is a pattern for determining whether a user is authorized to perform a certain action based on attributes associated with the actor or the subject of the action.

ABAC is a broad pattern that is a superset of many other authorization patterns, like RBAC and ReBAC. Both RBAC roles and ReBAC relationships can be thought of as attributes of the actor and the subject.

Most applications begin with an RBAC model, where users are assigned permissions based on roles. The role describes a person’s job, and the job determines what actions they can take.

In an HR system, RBAC might look like this:

RBAC is simple and works well when responsibilities map cleanly to job titles.

In contrast, ABAC determines what a user can do based on attributes, which could be facts about the user, the resource, or the situation. Continuing on our HR example, attributes could be things like a user’s department, region, employment status, or whether they are currently on leave. In ABAC, you can create more granular controls, such as:

At Oso, we see several common use cases and patterns for ABAC that help organizations implement fine-grained, context-aware access control efficiently. To make these patterns concrete, we’ll show examples using Polar, Oso’s declarative policy language. Polar allows you to write short, composable rules that are easy to read and maintain, separating your authorization logic from application code.

By representing access rules as policies in Polar and evaluating them against live attributes (facts) about users, resources, and the environment, Oso provides a centralized, consistent, and auditable way to enforce ABAC across your applications.

Below are some common patterns that arise when implementing ABAC in real-world applications:

In applications where certain resources, such as repositories, are shared among multiple users, there is often a need to distinguish between resources that are publicly accessible and those that are restricted. A resource, like a repository or file, might carry an attribute like is_public to determine who can access it.

Example in a code repository management system (like GitHub or GitLab):

actor User {}

resource Repository {

permissions = ["read"];

roles = ["contributor", "admin"];

relations = { organization: Organization };

}

# ABAC: public repos are readable by everyone

has_permission(user: User, "read", repo: Repository) if

is_public(repo);

# ReBAC/RBAC-style rules for non-public repos

has_permission(user: User, "read", repo: Repository) if

has_role(user, "contributor", repo);

has_permission(user: User, "read", repo: Repository) if

org_role(user, "viewer", repo); # assume org_role is provided by your app

Here, if the repository isn’t public, other rules (like membership or organization role) decide access. This avoids redundant roles such as public_reader and keeps access control flexible and data-driven.

While roles are still useful, they often need to be combined with conditions to be truly effective. For instance, a repository member may write only when the repository is public.

Example in a version control system (like GitHub):

actor User {}

resource Repository {

roles = ["member"];

permissions = ["write"];

# you might also declare: "write" if "member";

}

has_permission(user: User, "write", repo: Repository) if

has_role(user, "member", repo) and

is_public(repo);

Here, the role grants baseline access; the attribute refines when it applies.

Subscriptions and temporary access often expire, so instead of batch-updating roles, enforce expiry in the policy. For example, a user can access premium content only if their subscription hasn’t expired.

test "access to product is conditional on expiry" {

setup {

# Alice's subscription expires in 2033

has_subscription_with_expiry(User{"alice"}, Product{"pro"}, 2002913298);

# Bob's subscription expired in 2022

has_subscription_with_expiry(User{"bob"}, Product{"pro"}, 1655758135);

}

assert has_permission(User{"alice"}, "access", Product{"pro"});

assert_not has_permission(User{"bob"}, "access", Product{"pro"});

}

This way, the policy itself enforces expiry, and no one has to remember to clean up roles later.

In workflows such as financial transactions or security approvals (e.g., approving changes to network security configurations or access control policies), it is crucial to ensure that certain actions are segregated to maintain proper checks and balances.

For example, one user should not have access to both initiate and approve the same transaction or security change, avoiding potential conflicts of interest or unauthorized actions. Here’s a sample policy for that:

has_permission(user: User, "approve", txn: Transaction) if

initiated_by(txn, initiator) and

initiator != user and

has_role(user, "risk_management", txn);

This ensures checks and balances by separating responsibilities.

Not every user should see the same level of detail in a dataset. With ABAC, you decide what fields to reveal based on who is asking and the attributes of the data. A classic example is healthcare: doctors treating a patient may need to see full PII, while others may only see redacted values.

Many teams implement logic like this at the query layer:

SELECT

CASE

WHEN user.role = 'doctor'

AND user.department = patient.department

THEN patient.ssn

ELSE '***-**-****'

END AS ssn,

patient.name,

patient.dob

FROM patient;Doctors in the same department see the real SSN. Everyone else gets a masked value.

Here's how Oso addresses it: Instead of baking masking logic into every query or service, you shift the decision to the policy engine.

In Polar (Oso Cloud), the masking rule becomes:

actor User {}

resource Patient {}

# facts provided to Oso Cloud:

# user_department(User, Department)

# patient_department(Patient, Department)

has_permission(user: User, "view_ssn", patient: Patient) if

dept matches Department and

user_department(user, dept) and

patient_department(patient, dept);And at the time of implementation:

if oso.authorize(user, "view_ssn", patient):

return patient.ssn # full value

else:

return "***-**-****" # maskedNow the application never needs to remember when to redact; it just asks the policy engine. Conditional masking is a routine requirement in production systems. Whether it’s protecting PII, financial data, or case notes, the solution is always the same: evaluate attributes on every request and let the policy engine decide what to reveal, rather than hard-coding masking logic throughout the application.

On paper, ABAC looks simple and easy to implement. However, several challenges arise, so let’s walk through each of them briefly:

1. Attributes drifting out of sync.

ABAC decisions depend on clean data, as a missing or stale attribute breaks access. If HR hasn’t updated a user’s department, or if a document is missing its classification tag, the system makes the wrong call. Every attribute needs a clear system of record: HR for department, Security for clearance, and your app for is_locked. If you don’t pin ownership like this, you end up debugging access issues that are really data problems.

2. Too many attributes, no common language.

Different teams invent attributes as they go: one service tags dept=finance, another writes team=fin, another uses department=FIN. Now your policies don’t line up. Without a shared schema, you’ll spend more time mapping synonyms than writing rules. I’ve seen this kill ABAC rollouts because the same policy had to be re-implemented three different ways.

3. Policy sprawl.

RBAC gives you a neat table of roles and permissions. ABAC gives you conditionals. If you’re not careful, policies become chains of if user.attrA && resource.attrB && env.attrC… that no one can read or debug. When two rules overlap, you need a way to resolve conflicts. Otherwise, you’ll have users who can’t explain why they were denied, and developers who can’t explain why they were allowed.

4. Legacy systems don’t play along.

Legacy apps hardcode checks, so to make them query a Policy Decision Point (PDP), the service that evaluates access rules and returns an allow/deny decision, you either wrap them with a proxy or rewrite the layer, and both are expensive solutions. I’ve had cases where we left the legacy system on RBAC and only used ABAC at the API gateway, just to keep the lights on.

5. Latency from attribute lookups.

Each check may query HR, LDAP, or a database. Fetching attributes fresh on every request slows everything down. At scale, you need aggressive caching and a way to pre-load hot attributes; otherwise, “authorize()” becomes the slowest part of your request path.

6. Auditing is harder.

With RBAC, you can hand an auditor a role-to-permission map. With ABAC, every decision depends on current attributes. If you don’t log which attributes were checked and which rule fired, you can’t explain after the fact why someone was allowed or denied. That’s not optional in regulated environments.

7. Trust in attribute sources.

The system assumes attributes are correct. If the service issuing clearance=top_secret is compromised, the whole model collapses. That’s why in bigger orgs, attributes have to come from authoritative sources with controls on who can create or change them, and why you need governance around schema changes.

One of the most challenging aspects of ABAC is ensuring readable policies and reliable attributes. In home-grown systems, you often end up with:

Without a centralized policy engine, these challenges lead to complicated, fragmented code that’s difficult to manage and debug.

Oso Cloud addresses these problems by:

Oso addresses these issues by separating policies from facts:

- Facts: Live authorization data (e.g., User:Alice is an owner on Item:foo) is stored in a centralized location. Your services own the facts, but Oso evaluates them consistently across all requests.

- Policies: Written in Polar, Oso’s declarative language, rules are short, composable, and easy to read. Policies evaluate against facts to enforce access control without embedding complex conditionals in your application.

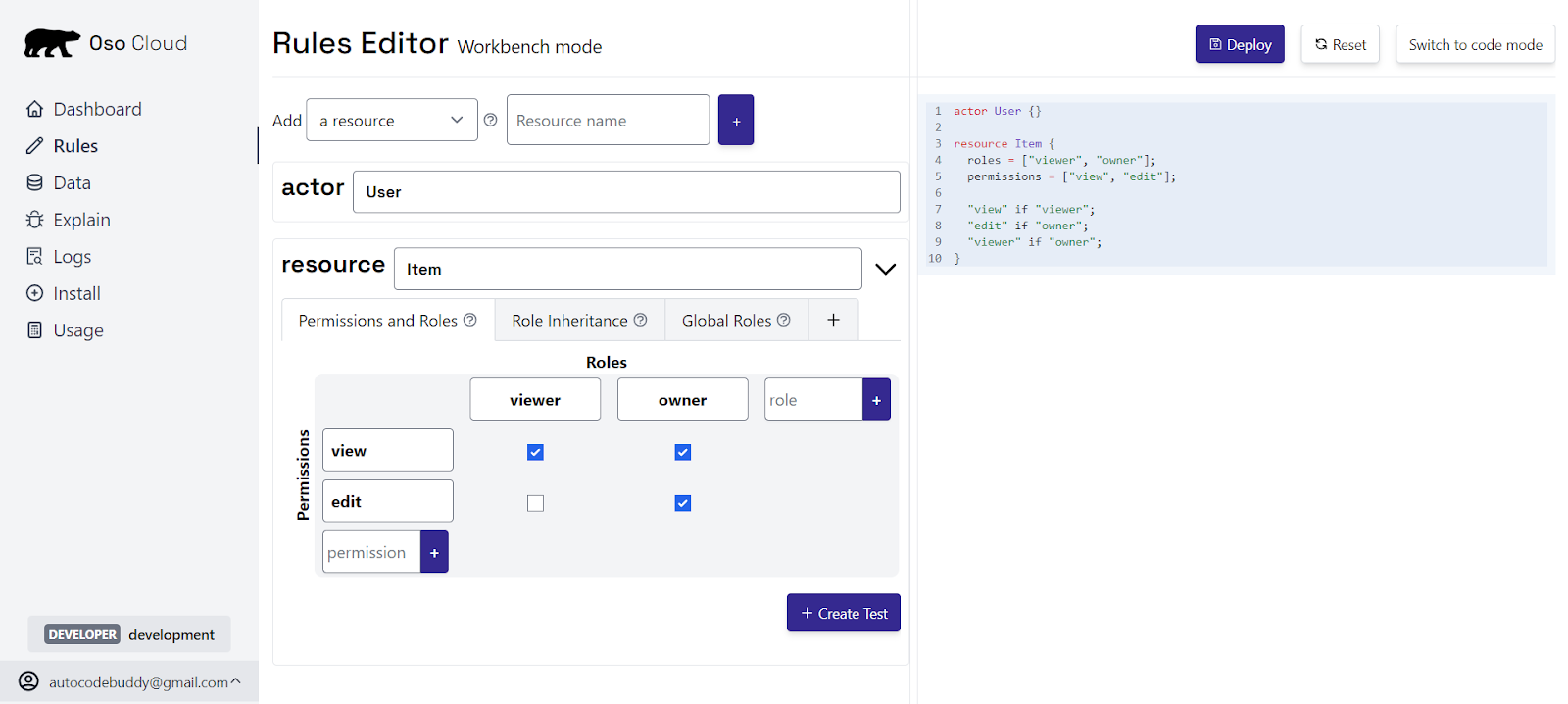

- Workbench Mode: Enterprise teams can define resources, roles, and permissions in a UI, which automatically generates the equivalent Polar rules, so you don’t end up with drift between environments or hand-coded rules scattered in services:

- Polar rules are automatically generated, preventing drift between environments or hand-coded rules in multiple services.

This centralized model ensures consistent, auditable, and maintainable ABAC enforcement across your applications.

Once policies and facts are in place, the Explain tab gives visibility into why access is granted or denied. Instead of manually tracing multiple systems:

“This user was allowed because is_public(repo) = true and they had the member role.”

Let’s see this in action. We’ll start by defining a User and a Repository in Polar, Oso’s policy language:

actor User {}

resource Repository {}

Every check is between an actor and a resource. Now let’s introduce a basic rule. Suppose a repository can be read if it’s marked as public. We model that with an attribute is_public and a rule that checks it:

resource Repository {}

has_permission(_user: User, "read", repository: Repository) if

is_public(repository, true);

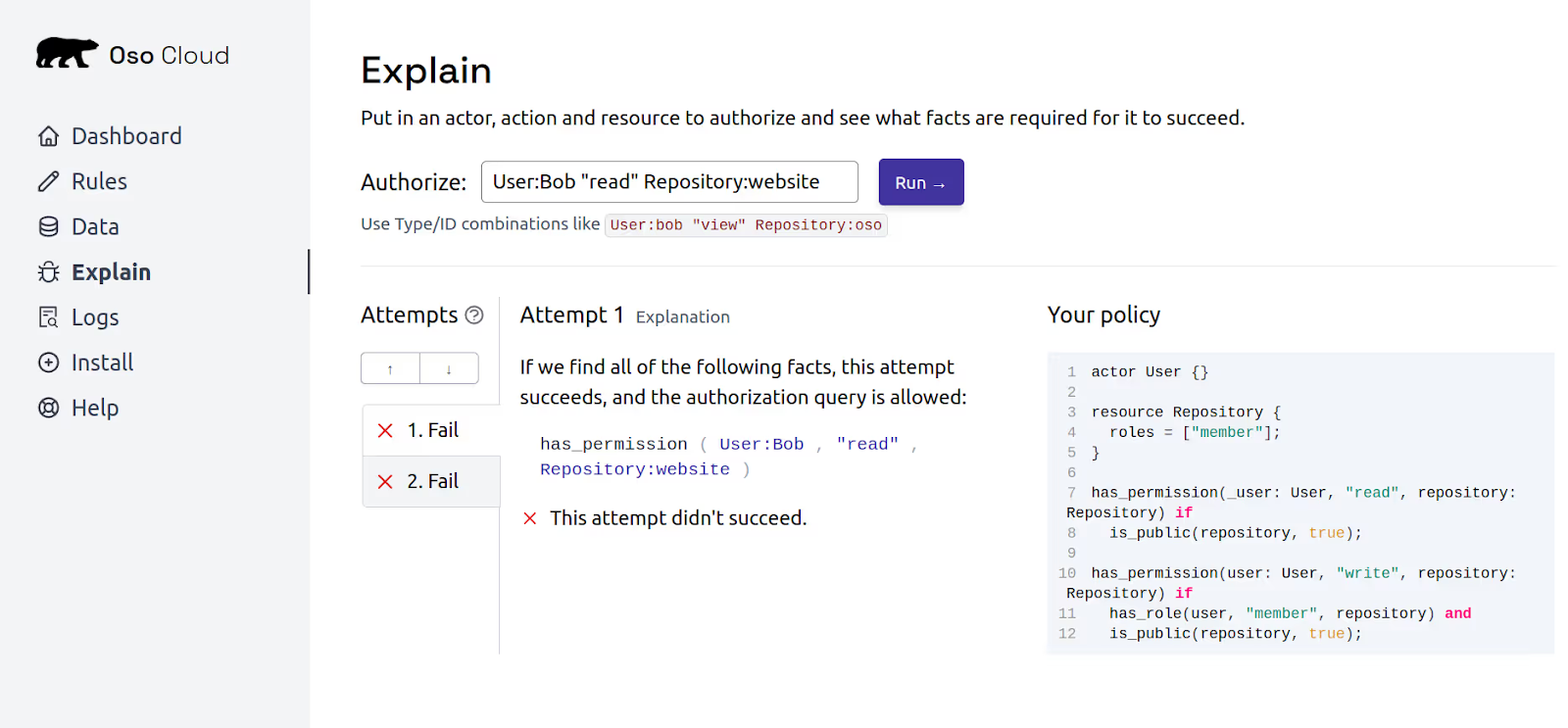

If we now ask whether Bob can read the website repo, the check fails. There’s no fact telling Oso the repo is public.

Navigate to Oso Cloud's "Explain" tab, which lets you simulate authorization queries. In Explain, run:

User:Bob "read" Repository:website

By default, the user Bob can't read the repository website because the repository website does not have is_public enabled.

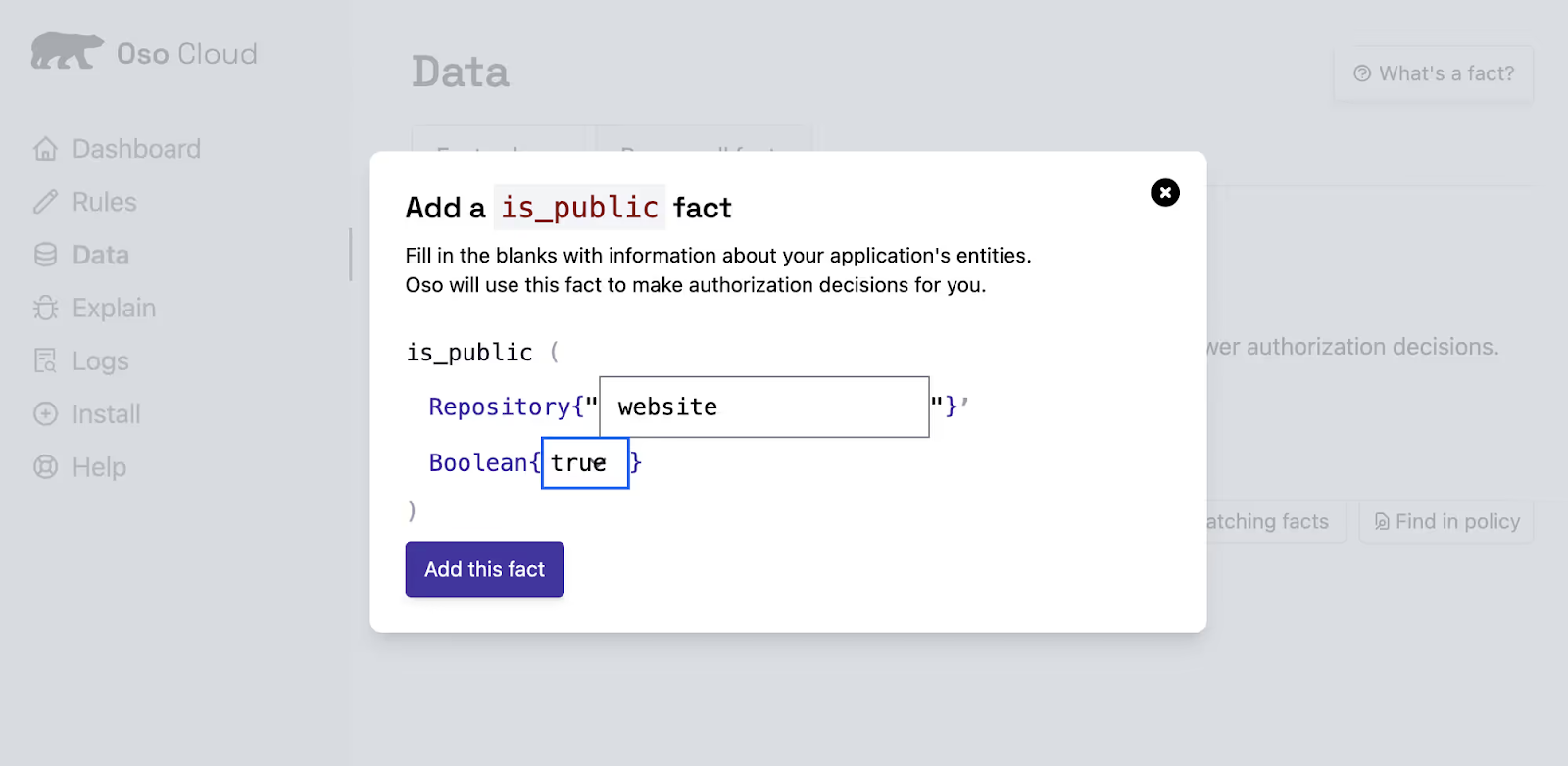

In Oso Cloud, facts are how you represent authorization data, including ABAC attributes. You can represent whether a repository is public as a fact. Navigate to the "Data" tab in the Oso Cloud UI, and add a new fact that indicates that the repository website has is_public enabled as true.

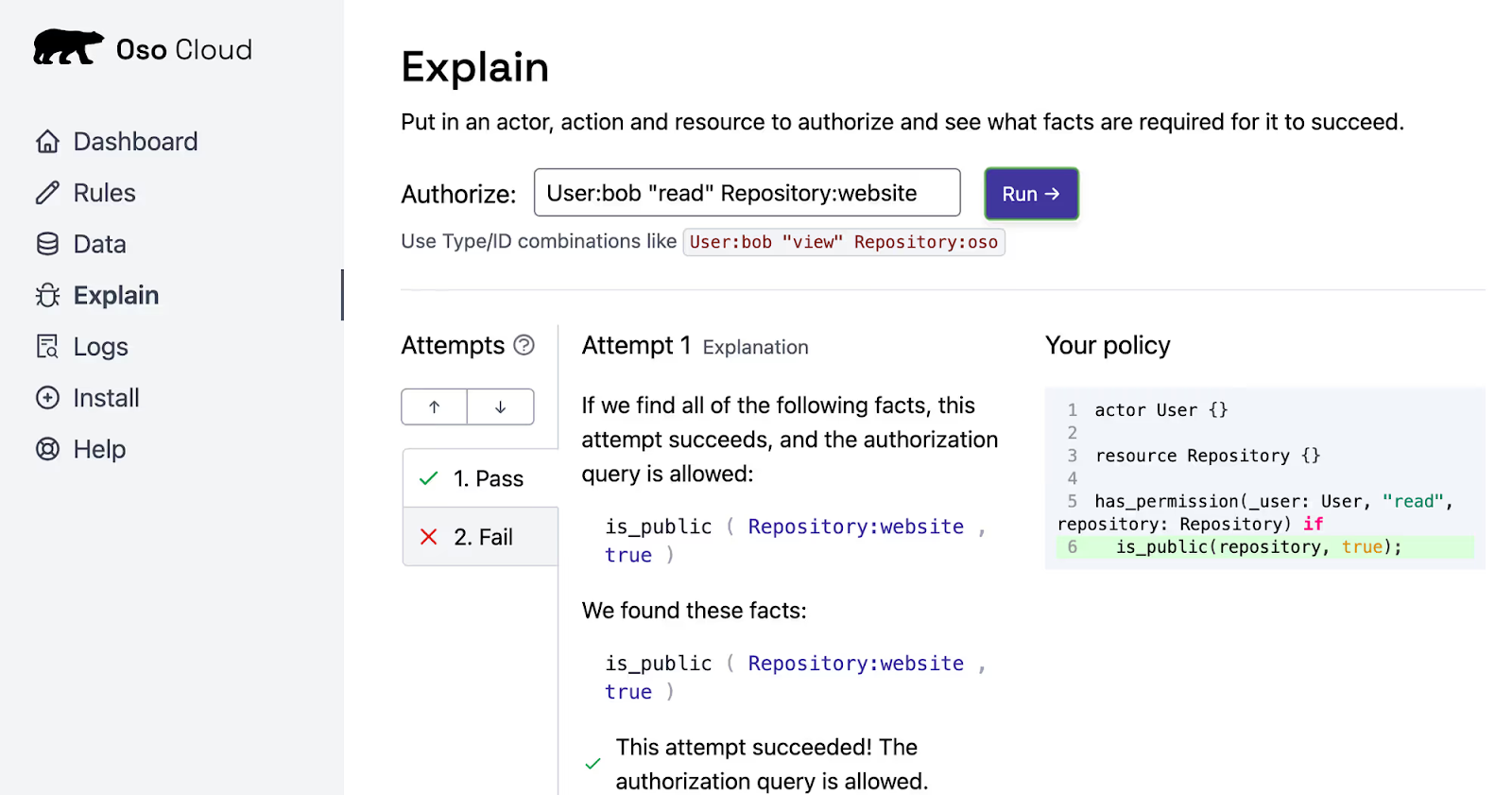

Now, navigate back to Oso Cloud's "Explain" tab, run the same query. Now that the repository website has is_public enabled as true, Oso Cloud can infer that the user Bob can read the repository website.

What changed? Not the policy, only the fact. That’s the ABAC advantage: decisions track live attributes without code edits.

The “users can read public repositories” rule is an example of the “Attribute checks” pattern from Oso’s 10 Types of Authorization blog post. Another ABAC pattern from that blog post is called “Attribute add-ons”, which mixes ABAC patterns with RBAC and ReBAC or relation-based access control.

For example, the following rule tells Oso that “users can write public repositories if they have the member role.”:

actor User {}

resource Repository {

roles = ["member"];

}

has_permission(user: User, "write", repository: Repository) if

has_role(user, "member", repository) and

is_public(repository, true);

Debugging access control decisions in ABAC can be challenging, especially when analyzing dynamic attributes. Without the right tools, you might struggle to determine exactly why a request was allowed or denied. Oso Cloud's Polar Playground addresses this challenge by enabling you to load your policies, add sample facts, and run authorization queries. Instead of guessing which attribute caused the issue, you can get a clear trace of the rule and fact combination that led to the decision.

Static roles work until context changes, resource state, time, or relationships. ABAC adapts to those shifts, offering real-time, fine-grained access control. However, implementing ABAC without proper tooling can lead to inconsistent attribute definitions across identity providers, cloud services, and application layers — plus overly complex policy logic that becomes difficult to maintain.

Oso Cloud addresses these issues by separating rules from data, defining policies in the Polar language, and providing the Explain tab for visibility into access decisions. This structure ensures consistent policies and debuggable rules.

Start small by modeling one rule, test it, and expand as needed. With Oso, you can scale your ABAC policies efficiently, ensuring flexibility without sacrificing maintainability.

What is ABAC?

Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) determines whether a user can perform an action based on attributes of the user, the resource, the environment, or the action itself. Attributes could include things like role, department, location, time of access, or data sensitivity.

What are the common use cases for ABAC?

ABAC is ideal for scenarios requiring fine-grained, context-aware access decisions. Common use cases include:

What makes ABAC challenging to implement?

Implementing ABAC can be complex because policies must account for multiple dynamic attributes, which increases evaluation overhead and requires careful governance. Maintaining accurate attributes and keeping policies consistent across systems is often the most difficult part.

Can RBAC and ABAC be used together?

Absolutely. Many organizations use RBAC for broad, role-based permissions and ABAC to enforce fine-grained, context-aware rules. This hybrid approach lets you define baseline access by role while dynamically refining permissions based on attributes.

How does Oso support RBAC and ABAC?

Oso supports hybrid access control, enabling RBAC, ABAC, and ReBAC in a single framework via Polar. You can combine static role-based permissions with dynamic attribute- or relationship-based rules, giving teams both simplicity and fine-grained control.